by Barbara Lach

Open data is just one of many digital dividends of new technologies, albeit an important one for modern participatory democracy. Other dividends include instant access to information, news, financial services, education, jobs, health services, social media and civic and political engagement. All these digital dividends have one thing in common—these benefits depend on broadband Internet access. Consequently, citizens who do not have Internet access, or 55 million Americans, can enjoy none of these benefits. For 17 percent of the population, open data remains closed, and with it the chance for civic engagement.

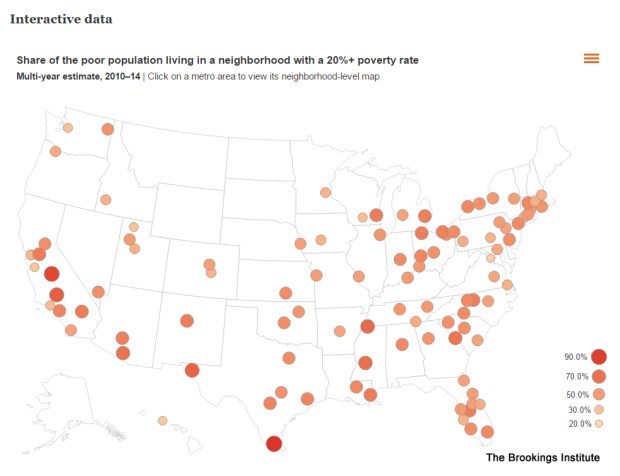

Driven by calls for greater government transparency, opening up of public information is a noble cause in itself. But citizens can take advantage of open data only if they can access and apply the data. Data for data’s sake is meaningless; only data that can be applied is meaningful. Data application, though, requires Internet access and knowledge. Because only those with an uninhibited access to technologies and education can apply data, they are the ones who learn and profit from open data first. When information becomes available, the rich profit the most, and the poor become not only poorer but also disengaged. This is the Matthew effect, or accumulated advantage, of open data.

Today 40 states and 48 localities provide data sets to the federal online open data repository. Open data, not to be confused with big data, means that public information is accessible online to the public—it becomes a public resource. The Open, Public, Electronic and Necessary (OPEN) Government Data Act that went into effect May 25 of this year requires the government to provide all public federal information in searchable open formats freely available to anyone online. Making public information accessible online allows citizens to understand how the government spends money, for example, and thus hold public elected officials accountable. Open data of procurement processes at all government levels could shed light on how the government buys goods and services from the private sector. On a local level, open data can benefit citizens through improved city services.

Participation in governance and the process of democratization that surround the movement to open data are subject to Internet access. Improved quality of life and government services remain just a promise for all those who cannot afford an Internet connection. For example, four in five households in inner Kansas City have no home Internet access, so application of open data is not even an issue for them. They simply have no data. They are excluded from the culture of shared public information.

Universal Internet access would expand opportunities and enable civic and political engagement for all. The Matthew effect means that those without access are not only denied the advantage of having information at their fingertips but also that they continue to fall further behind in terms of civic engagement. They are excluded from the participatory political process and the tech-driven government transparency–both predicated on Internet access—which makes the concept of informed and participatory citizenry elitist. Only the elite–the privileged and technologically savvy–enjoy open data dividends. The Matthew effect of digital dividends leaves almost 50 million Americans without a civic voice.